Some of the best, most succinct writing advice I ever received came from the great John McPhee, via one of his former students: “Writing is paying attention.” What do you see, hear, taste, etc.? Questions of style, syntax, and punctuation come later. Obsess over them before you’ve learned to pay attention, and you’ll have nothing of interest to write about. And in order to notice what you’re noticing, you’ve got to record it; so keep a notebook with you at all times to jot down overheard expressions, thrilling sights and insights, dramatic chance encounters… hoarding material, all the time.

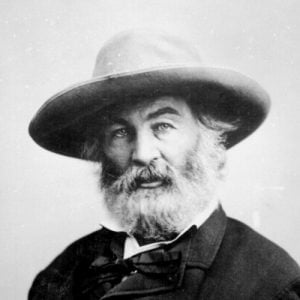

But he was also a hard-headed realist with a bent toward the utilitarian and a scrappy resourcefulness that made him an artistic survivor. Whitman contained multitudes, not only in his poetry but in his writing advice. When editors of The Signal, newspaper of The College of New Jersey, asked the poet in 1888 to advise young scholars on the “literary life,” he obliged, giving the paper a brief interview in which the “gray-haired, handsome, aged poet of Camden” proffered the following (condensed in list form below):

1. Whack away at everything pertaining to literary life—mechanical part as well as the rest. Learn to set type, learn to work at the ‘case’, learn to be a practical printer, and whatever you do learn condensation.

2. To young literateurs I want to give three bits of advice: First, don’t write poetry; second ditto; third ditto. You may be surprised to hear me say so, but there is no particular need of poetic expression. We are utilitarian, and the current cannot be stopped.

3. It is a good plan for every young man or woman having literary aspirations to carry a pencil and a piece of paper and constantly jot down striking events in daily life. They thus acquire a vast fund of information. One of the best things you know is habit. Again, the best of reading is not so much in the information it conveys as the thoughts it suggests. Remember this above all. There is no royal road to learning.

Whitman’s advice contains sound, practical tips on what we might today call “professionalization.” Should we take his admonishment against writing poetry seriously? Why not? For a good portion of his life, Whitman earned a living “whacking away,” as he liked to say often, at more utilitarian forms of writing, from reportage to an advice column. Whitman took seriously his role as a voice of working people and perhaps saw this interview as an occasion to address them.

Whitman’s “seething rejection of poetry,” writes Nicole Kukawski in the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review, should not surprise us; it is “simply part of his attack on conventionality in all respects… poetry can never be ‘utilitarian’—in no way can it reach the masses for their benefit.” Unlike our day, poetry was ubiquitous in late nineteenth century America, part of an entrenched, highly conventional polite discourse. Who knows, maybe a Whitman of the early 21st century would feel very differently on this point. Surely we could use a great deal more “poetic expression” these days.

Ajuda-nos a manter viva e disponível a todos esta biblioteca.

Whitman’s final piece of advice accords fully with John McPhee’s—and several hundred other writers and teachers. But in Whitman’s estimation, noticing, and acquiring “a vast fund of information,” was not only essential to the literary life but also key to pursuing an “individualistic,” real-world self-education. “One subject about which Whitman did not contradict himself,” writes Kukawski, “was his consistent belief that the scholar should learn by encountering life instead of reading books alone.” There may be no better exemplar of that philosophy in American letters than Walt Whitman himself.

O Artigo: Walt Whitman Gives Advice to Aspiring Young Writers: “Don’t Write Poetry” & Other Practical Tips (1888), foi publicado em Open Culture

The Post: Walt Whitman Gives Advice to Aspiring Young Writers: “Don’t Write Poetry” & Other Practical Tips (1888), appeared first on Open Culture

Assinados por Artes & contextos, são artigos originais de outras publicações e autores, devidamente identificadas e (se existente) link para o artigo original.