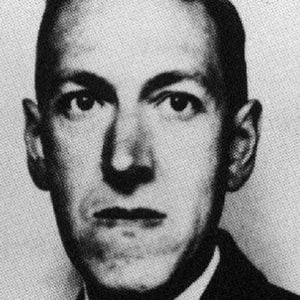

H.P. Lovecraft has somewhat fallen out of favor in many circles of horror and fantasy writing. Just this past year, after much debate, the World Fantasy Awards decided to remove his likeness from their statuette. Because, quite frankly, Lovecraft was not only a bigot but a committed anti-Semite and white supremacist who loathed virtually everyone who wasn’t, as he put it, “Nordic-American.” This included African-Americans and “stunted bracycephalic South-Italians & rat-faced half-Mongoloid Russian & Polish Jews, & all that cursed scum,” as he wrote in a letter to fellow writer August Derleth. The statement is representative of many, many more on the subject.

Were these simply private political opinions and nothing more, there might not be sufficient reason to read them into his work, but as several people have argued convincingly, Lovecraft’s opinions form the basis of so much of his work. China Miéville, for example, writes “I follow [French novelist Michel Houellebecq—hardly known for any kind of political correctness] in thinking that Lovecraft’s oeuvre, his work itself, is inspired by and deeply structured with race hatred. As Houellebecq said, it is racism itself that raises in Lovecraft a ‘poetic trance.’”

Lovecraft’s xenophobic loathing begins to seem like an almost pathological hatred and fear of anyone different, and of any kind of change in the nation’s makeup. It goes far beyond casual “man of his time” attitudes (and increasingly, of our time). F. Scott Fitzgerald lived during Lovecraft’s time. And Fitzgerald had the critical distance to satirize fanatical bigotry like Lovecraft’s in The Great Gatsby‘s Tom Buchanan. All of that said, however, it’s impossible to deny Lovecraft’s influence on horror and fantasy, and almost no one has done so, even among those writers who most vehemently lobbied to retire his image or who found his presence deeply troubling.

World Fantasy Award winner Nnedi Okorafor writes about contemporary authors having to wrestle with the fact “that many of The Elders we honor and need to learn from hate or hated us.” Winner Sofia Samatar, who wanted the statuette changed, exclaimed, “I am not telling anybody not to read Lovecraft. I teach Lovecraft! I actually insist that people read him and write about him!” In a short essay at Tor, sci-fi and fantasy writer Elizabeth Bear expressed many of the same ambivalent feelings about her “complicated relationship with Lovecraft.” While finding his “bigotry of just about any stripe you like… revolting,” his work has nonetheless provided “a powerful source of inspiration, the foundations of it like Hadrian’s Wall; full of material for mining and repurposing.”

It’s not particularly unusual to find such ambivalent attitudes expressed toward literary ancestors. All artists—all people—have their character flaws, and to expect every writer we like to share our values seems naive, narrow, and superficial. But Lovecraft presents an extreme example, and also one whose prose is often pretty terrible: overstuffed, overwrought, pretentious, and archaic. But it’s that pulpy style that makes Lovecraft, Lovecraft—that contributes to the feverish atmosphere of paranoia and alienation in his stories. “He’s a master of mood,” Bear avows, “of sweeping blasted vistas of despair and the bone-soaking cold of space.”

That much of his despair and horror emanated from a place inside him that feared the “gestures & jabbering” of other humans does not make it any less effectively creepy or hypnotic. It just makes it that much harder to love Lovecraft the author, no matter how much we might admire his work. But perhaps Lovecraft was such an effective horror writer precisely because he was so terribly afraid of change and difference. As he himself wrote of his particular brand of supernatural horror, or “weird fiction,” as he called it: “horror and the unknown or the strange are always closely connected… because fear is our deepest and strongest emotion.” One needn’t be a phobic racist to write good horror fiction, but in Lovecraft’s case, I guess, it seems to have helped.

Just as much as the work of Isaac Asimov, or Robert Heinlein, or Gene Roddenberry resides in the DNA of science fiction, so too does Lovecraft inhabit the organic building blocks of horror writing. Horror and fantasy writers who somehow avoid reading Lovecraft may end up absorbing his influence anyway; readers who avoid him will end up reading some version of “Lovecraft pastiche,” as Bear puts it. So it behooves us to go to the source, find out what Lovecraft himself wrote, take the good over the bad, even “pick a fight with him,” writes Bear, “because of what he does right, that makes his stories too compelling to just walk away from, and because of what he does wrong… for example, the way he treats people as things.”

Ajuda-nos a manter viva e disponível a todos esta biblioteca.

We’ve previously brought to your attention several online Lovecraft archives, such as this compilation of Lovecraft eBooks and audiobooks, and these many fine dramatizations of Lovecraft’s stories. Additionally, you can download many of Lovecraft’s stories and letters published in the seminal horror and fantasy magazineWeird Tales. And in the Spotify playlist above (download Spotify here if you need it), you can hear The H.P. Lovecraft Compendium, 23 hours of readings and dramatizations of Lovecraft’s creepy short stories and novellas, including The Shadow Over Innsmouth, “The Dunwich Horror,” The Whisperer in Darkness, “The Call of Cthulhu,” and many, many more. However repugnant many of Lovecraft’s attitudes, there’s no denying the power of his “weird fiction.” As the playlist advises, “you might want to leave a light on when listening to these chilling performances….”

O Artigo: 23 Hours of H.P. Lovecraft Stories: Hear Readings & Dramatizations of “The Call of Cthulhu,” “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” & Other Weird Tales, foi publicado em Open Culture

The Post: 23 Hours of H.P. Lovecraft Stories: Hear Readings & Dramatizations of “The Call of Cthulhu,” “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” & Other Weird Tales, appeared first on Open Culture

Assinados por Artes & contextos, são artigos originais de outras publicações e autores, devidamente identificadas e (se existente) link para o artigo original.