“Our intelligence, however lucid, cannot perceive the elements that compose it and remain unsuspected.”

“Nature, the soul, love … one recognizes through the heart, and not through the reason,” 16-year-old Dostoyevsky wrote in a beautiful letter to his brother. On some elemental level, we intuit this to be true, and yet we somehow let ourselves forget it as

a beautiful letter to his brother. On some elemental level, we intuit this to be true, and yet we somehow let ourselves forget it as

we grow older and more reliant on the intellect as our supreme mode of knowing. We seem to remember it only in moments of suffering — of emotional intensity so acute and uncontrollable that it strips down our rationalizations and deposits us, naked and unguarded, into the cradle of our own being. The wisdom of the heart that we reap in that vulnerable state is of a wholly different order than the intellectual insight we synthesize through deliberate rational thought.

This, perhaps, is what Rilke meant when he extolled sorrow as a supreme tool of self-knowledge and what Simone Weil, ever the underappreciated genius, was touching on in contemplating how to make use of our suffering. Yet what makes emotional suffering most anguishing is precisely that we so stubbornly resist it for, on some level, we judge it as anti-intellectual.

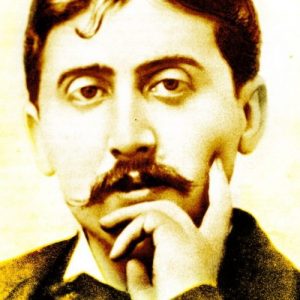

In The Captive & The Fugitive (public library), the fifth volume of his masterwork In Search of Lost Time, Marcel Proust (July 10, 1871–November 18, 1922) shines a penetrating sidewise gleam on this paradox of how the intellect, in its coolly rational search for facts, blinds us to the larger truths of our emotional reality.

Shortly after the protagonist has completed a rigorous intellectual analysis of his feelings for his romantic partner, Albertine, and concluded that he no longer loves her, he receives news of her death. He is suddenly overcome by such uncontainable and uncontrollable sorrow that the truth — a truth his intellect had rejected but his heart encoded far more deeply — was revealed to him: He does, after all, love Albertine tremendously.

In one particularly insightful passage, Proust channels through his protagonist, named after himself, universal insight into how our intellect blinds us to the wisdom of the heart and how pain, above all, strips down our intellectual defenses and puts us in raw, direct contact with the emotional truth of our being:

I had believed that I was leaving nothing out of account, like a rigorous analyst; I had believed that I knew the state of my own heart. But our intelligence, however lucid, cannot perceive the elements that compose it and remain unsuspected so long as, from the volatile state in which they generally exist, a phenomenon capable of isolating them has not subjected them to the first stages of solidification. I had been mistaken in thinking that I could see clearly into my own heart. But this knowledge, which the shrewdest perceptions of the mind would not have given me, had now been brought to me, hard, glittering, strange, like a crystallised salt, by the abrupt reaction of pain.

Ajuda-nos a manter viva e disponível a todos esta biblioteca.

Complement with philosopher Martha Nussbaum on the intelligence of the emotions, British economic theorist and philosopher E.F Schumacher on seeing with the eye of the heart, and Alain de Botton on what Proust can teach us about living more fully.

O Artigo: Proust on Love and How Our Intellect Blinds Us to the Wisdom of the Heart, foi publicado em Brainpickings.org

The Post: Proust on Love and How Our Intellect Blinds Us to the Wisdom of the Heart, appeared first on Brainpickings.org

Assinados por Artes & contextos, são artigos originais de outras publicações e autores, devidamente identificadas e (se existente) link para o artigo original.