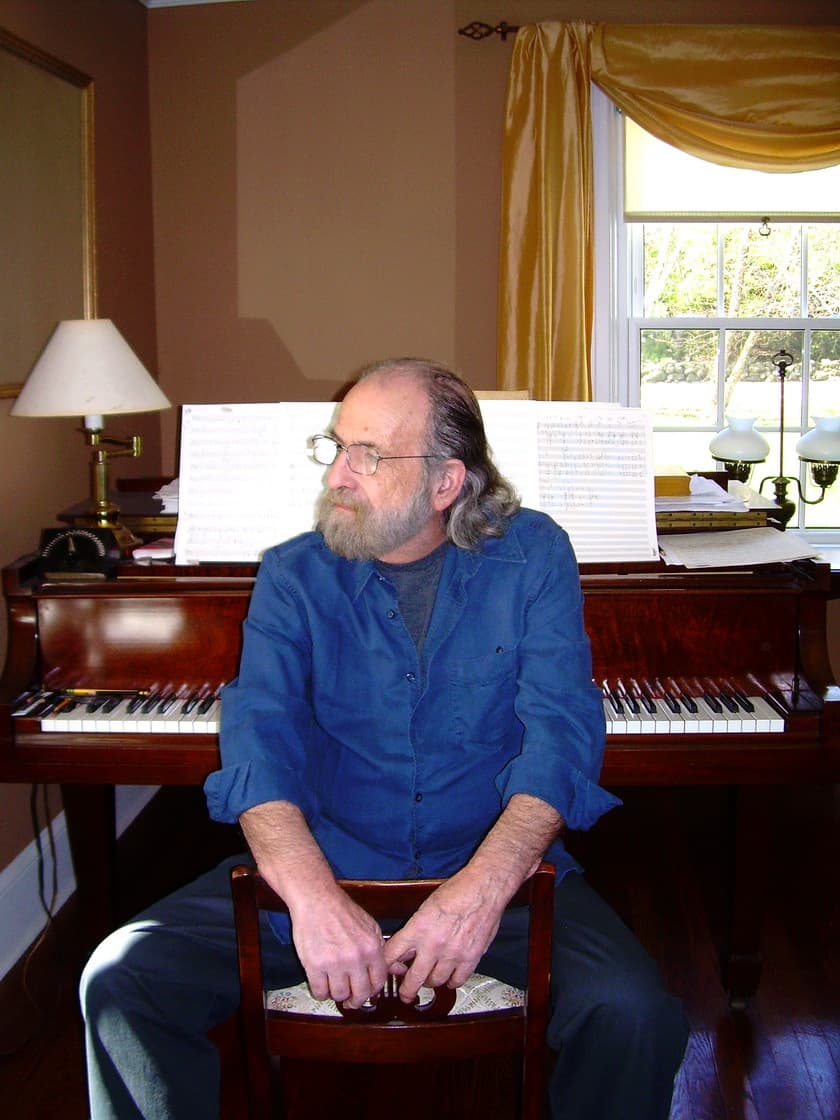

Richard Sorce

Richard Sorce took his first steps in music when he started learning the accordion at the age of eight, but he confesses that his preference has always been the piano. He told us that, according to his mother, since childhood he had his “ear glued to a radio” and that regardless of what other activity he had been involved in at the moment, when certain compositions were being broadcast, his full attention was directed to the music.

“From the beginning of lessons, I recall showing my father how certain assignments I was to practice sounded better when they were reharmonized or embellished with additional chordal factors. Truthfully, I didn’t know why what I was doing sounded better-since at the time I had no training in music theory and harmony.”

By the age of eighteen he finally started learning the piano (thankfully, I would say).

He has been on the faculty at Ramapo College and William Paterson University since 1999. He was on the faculty at New York as professor of theory, aural skills, and composition and director of the music theory program.

We asked him how does being a music teacher add to a musician’s life.

Richard Sorce. – Sharing our professional experiences with college music majors is a most gratifying experience, and one where we really are obligated to pass this knowledge on to the next generation of musicians.

He can remember the first piece he composed, but he also remembers that he later came to realize that it was a variation of an existing work that he had heard elsewhere.

But the first truly original piece, which he titled Windsong, is a solo piano piece.

Artes & contextos – Can you identify the moment when your creativity, associated with your personal taste, turned to Brazilian music?

R.S. – After my early years with the accordion, I moved on to piano and studied the classics; along with these lessons I also studied theory and aural skills. A few years after graduating high school I entered a conservatory as a piano major and subsequently as a theory and composition major. Even though my concentration was on the Western European Tradition, I also had an interest in jazz and current music and as a result formed the first of many bands in which I incorporated the “better” current music as well as several Brazilian pieces that were appearing on the Billboard Charts. It was at that time that I was inspired to try my hand at writing Brazilian influenced tunes. I believe the first Brazilian tune that caught my ear was Meditation. (Editor’s Note: Tom Jobim’s Meditação).

Bossambal Brazil, (Bossambal is a neologism created by Richard formed by: Bossa, Samba and Ballads) Richard Sorce’s fourth album, continues the path of exploration and reconfiguration of the Brazilian sounds that have long passionate him. Samba, Bossa Nova and Ballads are the source of inspiration and raw material for this, after all, jazz musician.

A&c – On this, your fourth album, you remain devoted to Samba and Bossa Nova. Do you adapt Brazilian musicality to your jazz, or do you adapt your Jazz to Samba and Bossa Nova?

R.S. – The latter.

This album is a voyage of 3 caravels in opposite direction, this time departing from Monte Pascoal loaded with Bossas, Sambas and Ballads. Sorce, the commander of this expedition, opts for the absence of words and aims for sweet harmonies, delicate arrangements and creates a sea of sugar for magical melodies and improvisations, of brass, pianos and guitars. Like a tuned sextant, at the helm we have a fabulous rhythm section, a yoga bass sound and translucent percussions.

The song Ballad for Claudio is one of those to listen to, listen to, and listen to.

A&c – The sound of Bossambal is notably different from previous records, starting with the bass that surrounds it and the way the drums shine in that background. Was it an aesthetic choice, did it happen by chance?

R.S. – When I go into a recording session I begin with piano, bass and drums only; unless there are specific bass lines or drum gestures, the musicians are reading from a lead sheet only (melody and chord changes). However, I will mention that every note is scored for the horn sections. Typically, we play through the piece once or twice, discuss it, and by the third pass it’s recorded as a “keeper.” The musicians I use are all full-time pros and can sight read virtually anything I present to them. Except when preparing for a live performance we rarely rehearse. On the last three albums, I have used the same drummer and bassist; I know them well and I know their interpretation will be what I’m after; occasionally, I will guide their performance but that doesn’t happen often. What one hears on the final master re: the sound of bass and drums is a result of mixing and of course the fact that I let the musicians play what they feel is the essence of the tune. So, I guess you might say it’s a bit of both: an aesthetic choice and a chance happening.

A&c – Bossambal Brazil is also a wordless album. Was it intended to leave more space for the melodic language of the instruments?

R.S. – Indeed. Except for a few areas containing vocalese, my intention with this album was to keep it virtually instrumental, with shorter solos, shorter length and wordless. I must admit also that over the years I’ve noticed that the lengthier tracks receive less attention on “commercial” radio, and I didn’t want the album to feature the voice which tends to gain the most attention on any recording.

Richard arranges his own songs, but if he could choose as he wishes, he would call Claus Ogerman to arrange them for him. As for playing live, he prefers jazz venues with audiences who would appreciate the “softer side” of jazz and prefers to play his songs by By the book except with extended solos.

A&c – What makes Bossambal Brazil a jazz album, and not a Samba, Bossa Nova or Ballads album?

R.S. – I don’t consider it a jazz album in the typical sense. Several reviewers over the course of the four albums have referred to my work as hybrid (I like that!). The fact that the melodies remain rather intact throughout the tracks and are not improvised in the way a jazz tune would be, disqualifies my work as typical of a jazz style; however, the solo or soloists’ sections are improvisations on the chord changes; some of these solo progressions are on the progressions supporting the melody/melodies of the tune while in many instances I’ll write a completely different chord progression for the soloist. So in that sense one could say that there is a jazz element in many of my arrangements. Re: Bossambal Brazil; it is the most “commercial” of the last four albums, e.g., the length of each track is rather short; the solos, when there are solos, are not extended; most tracks are in song form that is easily recognizable, and the element of vocalise on a few of the tracks serves as a bit of “ear candy.”

A&c – Some Brazilian authors from the 50’s and 60’s of the 20th century, as Jason Borge mentions in the paper Jazz and the Great Samba Debate, and Vice Versa argue that there is a blood tie between “Samba do morro” and early Blues and Jazz. Do you agree?

R.S. – Seems very likely in view of the hardships faced by these two indigenous populations.

A&c – Many of the main composers at the beginning of Bossa Nova, such as Laurindo Almeida, Luiz Bonfá and Garoto, had classical training and deep knowledge of harmony, however, some authors argue that Bossa Nova is the Jazzified Samba. What is your opinion about this?

R.S. – Personally, I don’t think Bossa Nova is a “jazzified” samba. As you know, there was great criticism by many Brazilians to the evolution of commercialized samba and of course, the whole concept of Bossa Nova. When one analyzes the melodic structure of many of the Bossa Novas that became popular, it’s obvious that it’s the harmonic underpinning of these often-simple melodies that makes them so appealing. I know these melodies are often heavily syncopated and that the harmonic content is often considered “jazz harmony,” but this is not jazz or “jazzified” music. Numerous Bossa Novas and Sambas have made the “commercial” charts in the past and continue to appeal to a wide international audience; unfortunately, this cannot be said of most jazz standards, and there lies the proof.

A&c – What has changed in the relationship and fusion between Samba and Jazz since Stan Getz and Charlie Byrd’s Jazz Samba of 1962 or Getz/Gilberto of 1964?

R.S. –

Over the years, it seems there is an over-abundance of virtuosic interpretation and presentation of jazz and samba standards, so much so that much of the beauty of the melody is lost in the apparent need of the performer to demonstrate her or his mastery of instrumental technique. My work and my recordings avoid much of this; the focus is on the melody, the harmony, the rhythm and the form, not on virtuosity.

Richard enjoys Literature and Painting and reads mainly Biographies, Philosophy and Science.

He writes Lyrics and have set many poems to choral music, but the poetry as such, no.

A&c – Don’t you ever imagine other words for the themes you interpret?

R.S. – No.

A&c – We listened to the album and the song of our choice is Ballad for Claudio, which we know has a story. Can you tell us some details about it?

R.S. – I met Claudio Roditi only a few years ago at the Blue Note in New York after he had called me at the suggestion of a mutual acquaintance. After the performance he and I sat for a while and discussed the performance at which time I subsequently handed him a copy of Samba para a Vida. A few days later he called again to tell me how much he enjoyed listening to the album and especially the first track, Escrito No Vento, telling me he started his day listening to that track! To my surprise he wrote Samba for Sorce. I reciprocated by writing Ballad for Claudio which he performed at Shanghai Jazz in New Jersey. We discussed his appearance on Bossambal Brazil, but as you know that was not to be. (Editor’s Note: Cláudio Roditi passed away in January 2020, at the age of 73).

Escrito No Vento went on to win Best Brazilian Song of 2017 on The Sounds of Brazil Radio in the U.S. I was recently informed by Claudio’s wife that Ballad for Claudio will become part of the archive she is in the process of establishing.

A&c – Nowadays in Brazil, when a beginner picks up a guitar, he already starts with an advance in harmonic terms that seems to be something born with him. How do you understand the fact that in the middle of the 20th century music in Brazil evolved to such complex harmonic structures, and how naturally this complexity spread to the whole Brazilian musical universe and was adopted by all musicians?

R.S. – Ontology: time and place. The sounds, or harmonic structures as we are discussing, are part of the collective Brazilian ear, just as the sounds of 18th Century Vienna were part of the Viennese ear, and just as the sounds of 21st century popular music are part of the “Millennial’s” and “Generation Z’s” ears, and on and on. As an example, no matter how erudite an American composer might be re: 19th Century Russian music, she or he would never be able to fully capture the essence of the Russian spirit; it’s just not in her or his ontological world. This might sound overly subjective, but I believe that the harmonic palette that exists in the Brazilian oeuvre is reflective of the expression of Brazilian views and passions.

A&c – Do you see jazz with Brazilian influences, with another suit of less conventional instruments?

R.S. – Aside from the proliferation of synthesized instruments, I don’t see any changes that might be coming from the use of current acoustic instruments. On my recordings the only synthesized parts are the strings (for now, at least).

A&c – Do you ever think, how much your music could be reformatted if you went to Rio de Janeiro, stroll through the Bairro do Estácio, where modern Samba flourished, to breathe the air, step into the streets and have a drink with the people who inspired it?

R.S. – I do occasionally, and once again I mention ontology. As a non-Brazilian, I don’t believe one could ever truly capture the essence of Brazilian music but being there could certainly have a profound effect on interpretation.

A&c – I suppose this record was made during the Covid19 pandemic, how did the encounters and disencounters with the rest of the musicians and technicians work out for its execution?

R.S. – The recording of Bossambal Brazil began during June 2019. I managed to finish all the tracking just before the “lockdown” and most of the mixing. However, the final mixes and the mastering had to be done remotely.

A&c – How do you fit into this increasingly generalized method, in which each member of the band records his or her part of the song, at their own homestudio, and then puts it all together for the final production? All of this remotely.

R.S. – The few times I tried this process of musicians recording tracks and sending files to later be blended with other musicians’ tracks proved to be far less “musical” than when at least the primary rhythm section (drums, bass, piano) were recorded together and then having other instruments, e.g., horn section, guitar, percussion, vocals and soloists overdub in the studio. So, to answer definitively, I do not care for, nor do I incorporate the process of sharing on my recordings.

A&c – Tell us a composer from outside your universe that you really appreciate.

R.S. – Virtually all the composers of the common-practice period, the romantic and post-romantic periods and the Impressionists.

(Editor’s Note: – Common-practice period, in the History of Music, is considered to span the years 1650-1910)

A&c – And a Band?

R.S. – Chick Corea; Earth, Wind and Fire; Banda Nova.

A&c – You create, compose, play, write, and teach. What do you do for fun, beyond music?

R.S. – Create, Compose, Play, Teach and write books; that’s it. For me, that’s all I need.

A&c – What would you ask Oscar Castro-Neves?

R.S. – I’d ask him if he thinks (as some do) or if he considers our styles similar.

A&c – Three people you would like to sit with on a terrace.

R.S. – Jobim, Beethoven e Debussy.

A&c – Thank you, be happy.

Text and interview: Rui Manuel Sousa and Rui Freitas

Translation and back-translation by: Bruno Freitas

Besides what has already been said, Richard Sorce is a published author, composer, and Billboard charted songwriter, arranger and producer, and has been on the faculty at Ramapo College and William Paterson University since 1999. Prior to his current positions he was on the faculty at New York University from 1980-1996 as professor of theory, aural skills, and composition and director of the music theory program.

He holds a Ph.D. in music theory and composition from New York University, an M.A. from NYU in theory, composition and higher education, and did undergraduate study at the Manhattan School of Music and the New York College of Music, as well as piano study at the Shenandoah Conservatory of Music.

Richard Sorce’s Website

Richard Sorce on Faebook

Ajuda-nos a manter viva e disponível a todos esta biblioteca.

You might be interested in: The Richard Sorce Project: Closer Than Before

0

Assinados por Artes & contextos, são artigos originais de outras publicações e autores, devidamente identificadas e (se existente) link para o artigo original.