This conversation with Pakistani Berlin-based artist and filmmaker Bani Abidi revolves around some of the core features of her substantial solo exhibition at Martin Gropius Bau in Berlin, curated by Natasha Ginwala and spanning two decades of her practice.

ANTONIA ALAMPI: I’d like to start by looking into the use of humor in your work—and at times irony—to address extremely complex and sensitive issues, in broad terms related to the entanglement of nationalism and its emergence within the colonial legacy, the bureaucratic apparatus, religious wrestling, cultural dislocation, and reterritorialization, in particular in relation to the history of South Asia and its diasporas. I perceive it as a commitment to humor for its social quality, for its capacity to bring subversive yet subtle elements and unexpected perspectives to an awareness that moves away also from victimizing or fetishizing narratives and gazes.

BANI ABIDI: I like that you ask about “humor and its social quality,” because a joke, like a verse of poetry, can abstract complex ideas and in some ways is instantly graspable, at least at the face of it. It is a democratic attempt at saying something. A humorous comment sticks in one’s mind because of its sheer brevity and returns to you again and again because it is layered in meaning, a play with fact. And both poetry and the tendency to satirize are very much part of the spoken street lingo in Pakistan, they articulate the mood of the city. You have to keep in mind that Pakistan went through eleven years of a dictatorship along with all other dictatorships in the ’70s and ’80s that were propped up during the Cold War. Obviously people figured out a way to deal and laugh in the process. One of my favorite examples of this kind of street humor is a verse painted on the back of a rickshaw in Karachi, which read in Urdu “Please don’t HONK, this nation is sleeping.” Rickshaw poetry—as we informally call it—is the work of amazing street poets who work in small shops that decorate buses and rickshaws. So you often come across jaw-dropping satire while being stuck in some traffic jam. And this becomes an anecdote that you repeat, and others repeat.

They Died Laughing

Bani Abidi © Mathias Voelzke

AA: I want to hold onto what you mention about the street and the mood of the city. An aspect that immediately caught my attention is the way in which you think about film in terms of space, and how urban space and its social texture are so incredibly entangled in the films themselves. While the retrospective of a filmmaker in an exhibition space can easily become a very homogenous spatial ground, in your case film feels deeply connected to volume and bodies. Could you tell me more about this?

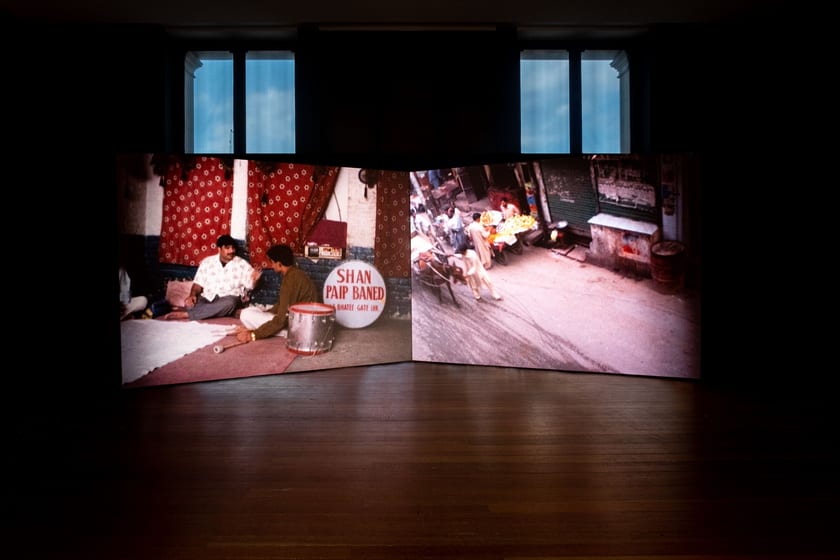

BA: In thinking about my video installations, the possibilities of specific material and spatial relationships are quite important, along with the projections themselves. I guess it has to do with the fact that I was educated in an art school and not a film academy. So the way a work sits in a space, and what else it speaks to, is inherent to my imagination of it. Just the small gesture in my film RESERVED (2006), of a small screen with a VIP motorcade next to a larger screen with scenes of people waiting for that motorcade to pass, is a decision about scale, which physically emphasizes the scene that I want to foreground. Death at a 30 Degree Angle (2012), similarly, consists of two vertical projections, which are each three meters tall, the idea always being to dwarf the viewer, much like they would be while looking up at a monumental statue. Funland (Karachi Series) (2014) is an assortment of six freestanding video screens, in which you can view the projection from either side. But in this arrangement, while the videos are vignettes of urban desolation in themselves, they also become inhabited by the moving shadows of the audience. I can only ascribe this tendency to my interest in physical structures and sculpture.

They Died Laughing

Bani Abidi © Mathias Voelzke

AA: I am curious about your formal references as well. Who—from filmmakers to artists and writers—would you say has influenced your practice?

BA: There are many, varied sets of influences, but there are certain filmmakers who I keep on returning to. Elia Suleiman, the Palestinian filmmaker (who for obvious reasons, still shockingly so, is not very well known in Germany) is someone who continues to delight me. His film Divine Intervention (2002)—which is about the absurdity of life under Israeli occupation—was literally what sealed the deal for me, in terms of continuing to work with the moving image. I was amazed to see how human nastiness can be reduced to satire, a way to highlight the pathetic, groveling acts of power and cruelty. His films are silent sequences of quotidian scenes in a neighborhood in the West Bank that the camera keeps on returning to. Each gesture of the characters is carefully choreographed and repeated till it develops and forms a narrative, just simple, absurd things to do with tensions between neighbors, for instance. His films seem to come from an archive of ordinary urban anecdotes that he has compiled over years of living in or visiting Palestine. But once put together in the form of a film, these moments form a highly subtle, theatrical narrative.

They Died Laughing

Bani Abidi © Mathias Voelzke

AA: I also would like to go back to the title of your show, which, as is written in some exhibition text, responds to William Shakespeare’s pun “to die laughing.” I had to think of another reference—namely a poster that became quite widespread in Europe—originally commissioned by them Soccorso Rosso Militante in the 1970s in Italy, in which the smile of an anarcho-syndicalist who was arrested in 1905 in Paris becae the visual symbol of the motto “una risata vi seppellirà” (a laugh will bury you). I guess by that I would like to discuss with you the role that death—in relation to threat, to laughter, and to immortality—plays in your films.

BA: That reference to laughter as a form of agency comes from a novel I was reading a while ago. The novel is called The Weary Generations (1963), by Abdullah Hussain, and it’s set in India in the first half of the twentieth century. The initial bit is about the conscription of Indian soldiers by the British for the First World War. It’s a moving and very disturbing account of that time. In one scene, young Indian soldiers are sitting on a battlefield on the Western Front in Belgium, cold and surrounded by dead bodies of their compatriots, but they are laughing about some anecdote about a lost buffalo in their village in India. Someone asks in wonder what could possibly be so funny. And one of them says, “We too are going to be killed, so we might as well die laughing.” And that scene really shook me. I kept on thinking about the insistence of these men to remember what they wanted, and to die as they wanted. How they must have infuriated the enemy with laughter. So the thought of laughing at power in order to reduce it to its base idiocy is a common and highly effective form of protest. Always has been. The motto “una risata vi seppellirà” of the Italian 1970s movement is just that. Thanks for telling me about that.

They Died Laughing

Bani Abidi © Mathias Voelzke

AA: And last, while your exhibition has been on, the situation of Kashmir has escalated, something perhaps in the making for years, which questions again the geopolitical situation of the region, encourages reflections on the legacy of colonial occupation, chronicles the growing sectarian violence, nationalism, and patriotism that your show undoubtedly—at times subtly and softly, at times more directly—addresses, particularly in your works from the late 1990s or early 2000s. I am not asking you to comment on it, perhaps just to share reflections, as I can’t help bringing this up considering how many topics your work unveils that are so meaningful to what is happening.

BA: These games of hatred production across the world are such an insult to our intelligence, yet people seem to be happily participating in them. The bar of intelligent political discourse has been lowered to such an extent it’s lying in the gutter. It’s becoming more and more farcical. The absurdity of it all is so in your face, and ripe with possibility for satire, but these days the onslaught is so aggressive that laughter seems to be fading away. In the past, I have played with questions of power and nationalism because it was just part of a more complex life of two fragile young countries. The ways we negotiated or made fun of the other were almost endearing. Now it’s aggressive and loud, and alliances have been made that are shocking—for God’s sake, there are conferences about Zionism and Hindutva being hosted by the Israeli embassy in Delhi! The script of what is to unfold is horrifying.

Ajuda-nos a manter viva e disponível a todos esta biblioteca.

Featured image: Bani Abidi, Funland’ (Karachi Series II) (still), 2014

Courtesy: the artist & Experimenter, Kolkata. Photo: Mathias Völzke

O artigo: “They Died Laughing”: Bani Abidi at Gropius Bau, Berlin, foi publicado @Mousse Contemporary Art Magazine

The post: “They Died Laughing”: Bani Abidi at Gropius Bau, Berlin, appeared first @Mousse Contemporary Art Magazine

Assinados por Artes & contextos, são artigos originais de outras publicações e autores, devidamente identificadas e (se existente) link para o artigo original.