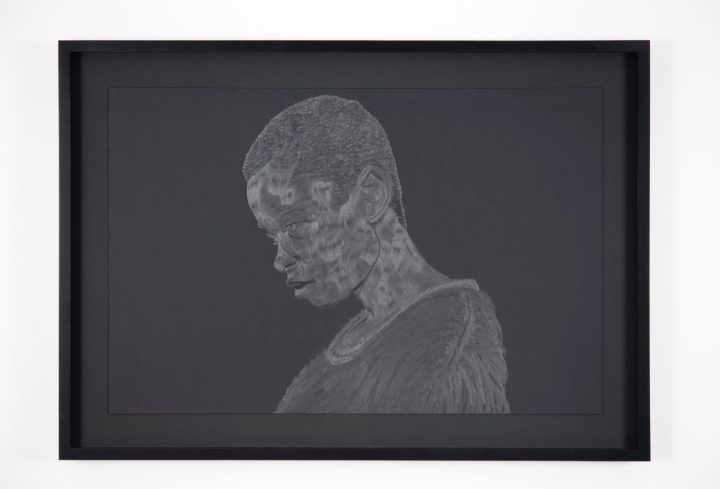

Fearuted image – Installation view of For Opacity at the Drawing Center, all work by Nathaniel Mary Quinn (all images courtesy the Drawing Center)

For Opacity exhibition at the Drawing Center several times, each time, except perhaps for one, seeing the work refracted through the mediating lens of language. Particularly because this show, in the words of Claire Gilman — the center’s curator who organized this exhibition — is about “the right to refuse self-revelation and classification … to not be understood,” it brings to mind provocative questions about how visual art in a public setting can weave in and out of obscurity and recognition.

Let’s start with all the ways I saw the show (in the order of experience): attending the December public conversation between Zadie Smith and Toyin Ojih Odutola; walking the show by myself on a winter’s night when I was mostly alone in the gallery; speaking to Gilman on the phone to fill in some gaps in my memory of the talk; and reading Gilman’s catalogue essay, “For Opacity: Elijah Burgher, Toyin Ojih Odutola, and Nathaniel Mary Quinn.” In each instance the exhibition read differently to me, and the differences conveyed to me that creating the intellectual tongs by which to grasp slippery meaning actually does at times give me purchase, and at other times fools me into grabbing something else which I mistake for the work.

I think of the moment during the chat between Smith and Odutola when the author and critic said that she thought the pieces done in white pastel were meant to “make whiteness strange to itself,” and Odotula blossomed with excitement, nodding her head repeatedly and saying “Yes, yes, yes.” In that instance I knew that the language of insightful critique had given to the maker of the work something in the work that she could not herself see. That felt discernment and enthusiasm felt like it earned the entire evening, but then there was more.

I had seen Toyin Odutola’s work several times before, including her most recent show at Jack Shainman gallery, When Legends Die, and the previous show at the Whitney Museum of Art, To Wander Determined. I thought that the show at Shainman was rushed, that several pieces lacked the fineness of control and rendering that has become associated with Odutola’s practice, but the Whitney Museum exhibition was quite strong, but held together by rhetorical scaffolding that was conceptually rather thin (depicting a fictional family that was wealthy and traveled the world). That experience gave me some lingering misgivings about her work post-To Wander Determined. But in talking with Smith, Odutola was articulately adamant about how complex her picture making is. She discussed her purposefully staking out the territory of the picture frame and creating quadrants where the colliding patterns of the background pushed the figure forward so that she or he might float above, more available to the eye, borne aloft by design and by craft. I can see this in her “Paris Apartment” (2016-17) where the figure’s face rises above the tide of her complicated dress fabric, the greenery of the wallpaper behind her, and the geometric lines described by the furniture left in her wake. Odutola spoke convincingly of exhausting the capabilities of ball point pen and finding herself having to move onto using the tools of pastel to keep her practice awake and alive to herself. Given what the artist said that evening, I now am able to see her work in more nuanced appreciation. I appreciate having the opportunity in my role as an art critic to revise my estimations, understanding that artists’ knowledge of their own craft can also educate me.

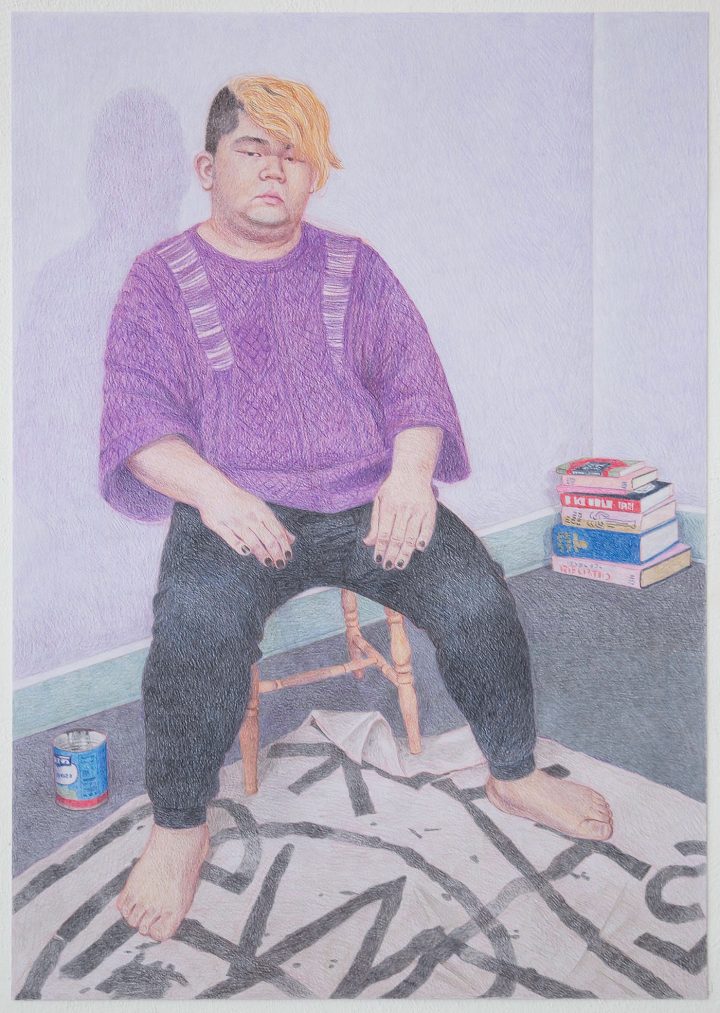

But then I visited the center on a quiet Friday evening by myself and saw Elijah Burgher’s drawings done with color pencil in pastel tones of figures interspersed with what looked like modernist design motifs tracing a visual lineage back somewhere between Paul Klee and Hilma Af Klint. The figures are inert, lacking urgency or care, though they are carefully and finely rendered. His work read as slack to me, having given into the entropic drift of our culture, refusing to be earnest or in any energetic way, present. Looking at “Mark” (2017), I thought that the gaze of the figure mirrored my own earned indifference to work: It is vacant, giving me nothing to grasp or interpret, while the runic symbols on the sheet beneath his feet are similarly opaque to me.

Nathaniel Quinn’s work, on the other hand is dynamic in its urgency to remake the human visage into something hybrid and incalculable. In “Golf Mound” and “Fixin to Eat” (both 2017), as in most of his work I’ve seen, the characters have mixed eyes, noses, and lips, the features that regardless of (surrounding) skin color act as racial signifiers. The work is playful, but it’s also vehemently resistant to being pinned down to a definitive version of Blackness. For him Blackness has a mercurial morphology though it is, in the public consciousness, linked to certain persistent notions, such as physical power and brutality. With the piece “King Kong Ain’t Got Nothing on Me” (a paraphrase of one the key monologues uttered by Denzel Washington’s character in Training Day, a film very much about a Black man who uses violence to subjugate a community) these associations are made vivid with fur and an ape’s hand grafted onto a human figure. However, his work looks like a great deal of collage I have seen in the last few years and seems to make the same points about hybridity and evading the gaze that attempts to definitively define.

Soon after, I spoke with Gilman on the phone and she informed me that Quinn drew every piece in the show. The work only looked like collage as Quinn’s skillful hand works through several media: charcoal, colored pencil, pastels, and ink. Gilman divulged that Quinn covers over parts of the work as he develops a piece, so that what he’s done previously is not visible — like playing the exquisite corpse game with himself. And while it felt important to understand this key element of the work, knowing this did not enlarge its meaning for me.

I returned to the exhibition one last time by reading Gilman’s essay included in the show catalogue, “For Opacity: Elijah Burgher, Toyin Ojih Odutola, and Nathaniel Mary Quinn.” Here Gilman explains that the title for the exhibition comes from an essay by Édouard Glissant who makes the argument in essence that “the oppressed or the historically constructed Other can and should be allowed to exist as different and unassimilated.” This is a powerful conviction, one so strong that it becomes the demiurge for a set of politics that undergirds the show, but these are somewhat sloppily applied to the work displayed. Gilman cites contemporary examples to make the argument for refusing transparency as a primary mode of being: the misuse of White empathy for Black subjects; the refusal to explain oneself constituting an essential aspect of privilege; the countervailing embrace of secrecy in queer community versus the emancipatory action of coming out of the closet. She concludes: “In all these situations, the obduracy of withholding becomes a critical stance.” Perhaps. But this begs the question whether the act of withholding information from the viewer is a useful one in this show. Burgher’s work, in particular, doesn’t bloom in this sun. His private, abstract sigils that are readable only to the artist and those with whom he has shared his coded schemes of queer desire. It’s fine for Burgher to have secrets that are obscure to me, but that leaves me with little to feel or gather from his drawings.

Ajuda-nos a manter viva e disponível a todos esta biblioteca.

The question that Gilman does not pose, and which her essay really needed to, is how members of marginalized groups decide who to let in on their secrets. The key questions are how these artists settle on the terms of intimacy they construct with the viewer, and for each artist what those terms are. Merely refusing to explain oneself, refusing the possibility of recognition clearly is not what these artists do. Rather, they make conscious and consequential decisions about how they want themselves and what they create to be seen. The writing and conversation convened around this exhibition at times helped me to see them in those enlightening ways, and at other times left me wandering in a kingdom in which I was only a stranger.

O artigo: Drawing Meaning Out of Art with Conversation, foi publicado @Hyperallergic

The post: Drawing Meaning Out of Art with Conversation, appeared first @Hyperallergic

Assinados por Artes & contextos, são artigos originais de outras publicações e autores, devidamente identificadas e (se existente) link para o artigo original.