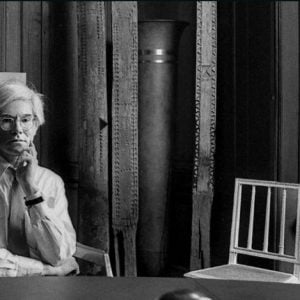

In the fall of 1968, still aching from an assassin’s attack, Andy Warhol returned to work in the bright new offices he’d rented on Union Square. After years of stardom in Pop Art, he pondered his future. “I was confused because I wasn’t painting and I wasn’t filming there,” he recalled.

Instead, he watched his minions taking care of business. They were shooting movies under his name, selling his prints and finding him portrait commissions — one way or another, making money with art. “I knew that work was going on, even if I didn’t have any idea what the work would come to.”

That corporate work, Warhol soon came to realize, was actually some of the most important art he ever made. Business Art, he came to call it, “the step that comes after art.” It established that everything this artist had done or would do, as head of Andy Warhol Enterprises, Inc. — as portraitist, publisher, publicist or salesman — counted as components in one boundless work: part performance art, part conceptual art and part picture of the market world he lived in and that we all still inhabit.

Now the Whitney Museum of American Art is about to open a major new Warhol survey. Titled “Andy Warhol — From A to B and Back Again,” it stars a full cross-section of his epochal creations: The Soup Cans and Marilyns of the early 1960s, which held up a mirror to American commodity culture; the experimental films of his Factory years; the society portraits, homoerotica and almost-abstractions of his last two decades. All treasures, without a doubt, but maybe just as significant for the times we now live in as aspects of his Business Art project.

The heart of Warhol’s idea — that by playing the role of businessman, an artist could turn himself into the latest, living example of a commodification he believed none of us can avoid — was perhaps as revolutionary in its time as Marcel Duchamp presenting a humble urinal as sculpture had been in 1917. Duchamp’s gesture declared that artists alone get to define what is art; five decades later, Warhol took that as permission to treat the spreadsheet, press release and launch party as creative endeavors. This set an example for some of his most notable heirs in our current century.

“I’ve wrestled with money — in an art sense — all through my career,” Damien Hirst, the longtime British art star and entrepreneur, said. “And I saw through Andy Warhol that it was possible to do that, that it was acceptable. Even though it raises questions, it’s not something to be afraid of.”

IN A RECENT INTERVIEW, the writer and curator Jack Bankowsky said, “Business Art remains as important as it ever was, because Andy Warhol is as important as he ever was.” In 2009, he organized a landmark exhibition called “Pop Life” for the Tate Modern museum in London that was about how Warhol’s decision to turn the marketplace and the publicity machine into artistic mediums has touched today’s major figures.

Alongside Warhol the show presented Jeff Koons, and the hard coreimages of sex with his wife that catapulted him to tabloid fame and to a corporate-scaled practice that even Warhol would envy.

Mr. Hirst was also central to “Pop Life,” not because of famous art objects like his shark-in-a-tank, but for the blockbuster auction he staged of his own works in 2008, an artistic “performance” most important for the more than $200 million it brought in. Although, as Mr. Hirst said, it would still have counted as an artistic win regardless of sales, “I knew I was pushing something to the breaking point, whether it succeeded or failed.”

The purest example of post-Warhol Business Art may be the work of the Japanese artist Takashi Murakami. At the Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills, Mr. Murakami is currently showing collaborations with the fashion designer and music producer Virgil Abloh, now in charge of the men’s wear line at Louis Vuitton; the art on display involves mash-ups of the duo’s brand names and trademarks.

In a pioneering 2007 essay on Mr. Murakami, Scott Rothkopf, the chief curator at the Whitney Museum, wrote about how capitalist business models are at “the very core” of everything that artist has done. Mr. Rothkopf, who did not organize the museum’s Warhol show, said that by infiltrating the market systems that shape our society, artists can help us see them more clearly. Part of Warhol’s greatness, he said, lay in his “prescient understanding” of how art would come to play such a role.

Without Warhol’s precedent we might not have seen the Oxxo convenience store that the Mexican artist Gabriel Orozco installed last year inside his dealer’s gallery in Mexico City. Hundreds of the store’s beer bottles, chocolate bars and mole jars had their labels dressed up with stickers of fractured circles, signature details from the abstractions that Mr. Orozco normally sells to collectors. The conflation of popular and high-art commodities was classically Warholian. So was Mr. Orozco’s sale of a good part of his shop’s stock to a major museum in Hong Kong.

And yet Warhol, the Business Artist set such a “strange, exciting, almost toxic example,” said Mr. Rothkopf, that many artists have found him a hard act to follow. Business Art so thoroughly rewrote the rules of art-making, even maybe its morality, that many artists found more direct inspiration in aspects of Warhol’s art that are less conceptual — his techniques, his grasp of pop culture, his pioneering work on gay and transgender subjects and culture.

But the effects of Warhol’s corporate model may run so deep that they aren’t always obvious. In the decade since his “Pop Life” show, said Mr. Bankowsky, Business Art has penetrated ever more deeply, as “the back story” behind of any sophisticated artistic practice. A show of paintings that look like straightforward aesthetic objects may just as easily be intended to address how art circulates and sells.

Ajuda-nos a manter viva e disponível a todos esta biblioteca.

“I think it’s impossible to make art today without somehow taking that on board,” said Mr. Hirst. “I think business in art is more important than politics.”

Last month, right after a work by the street artist Banksy sold for a record price of $1.4 million, the painting was destroyed by a remote-control shredder the artist had built into its frame. The art world, reared on Warhol and Hirst, immediately entered into a debate about whether Banksy was critiquing the art market or was complicit with it. His act might have simply been intended to increase the work’s value.

O artigo: When Andy Warhol Realized That Everything He Did Was The Art, foi publicado @ArtsJournal

The post: When Andy Warhol Realized That Everything He Did Was The Art, appeared first @ArtsJournal

Assinados por Artes & contextos, são artigos originais de outras publicações e autores, devidamente identificadas e (se existente) link para o artigo original.