In a world where the ubiquity of the cell phone camera has put the simple act of long looking on the endangered list, art that brings us back to a full-sensory apprehension of what the poet Mary Oliver calls “the summoning world” acquires new agency.

The young painter Daniel Heidkamp’s current show of plein air landscapes entitled Boston to Brooklyn at the Half Gallery on the Upper East Side of Manhattan offers a refreshing return to a fundamental impulse for making art: to deliver a felt response to the visible world. Encountering such tactile records fusing hard looking, mark-making, and emotional punch awakens a visceral sense of “being there” that can make us fall in love with painting all over again.

Ironically, the catalyst for the paintings in this show grew out of a digitally inspired curatorial project exploring the impact of mobile-phone cameras on photography, now on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York — Talking Pictures: Camera-Phone Conversations between Artists. Twelve pairs of artists, including Heidkamp, were invited to conduct a visual conversation through mobile phone images over a six month period; Heidkamp teamed up with the painter Cynthia Daignault who also works from life.

Between November 2016 and April 2017, Heidkamp and Daignault embarked on separate road trips and made paintings of places traveled, sharing images of their work via Instagram while en route. The selection of small square paintings (reflecting the Instagram format) in the Boston to Brooklyn are drawn from 30 that Heidkamp made during his Talking Pictures road trip.

It is curious to note that the Talking Pictures exhibition, designed to focus on new art generated by cutting-edge technology has, for Heidkamp, reinforced the value of an artistic practice that predates photography. While the result of his collaboration with Daignault at the Met is an expansive wall grid of enlarged Instagram photos (of their paintings), Heidkamp was clear from the start that his objective was always to use the project as a strategy to make new paintings.

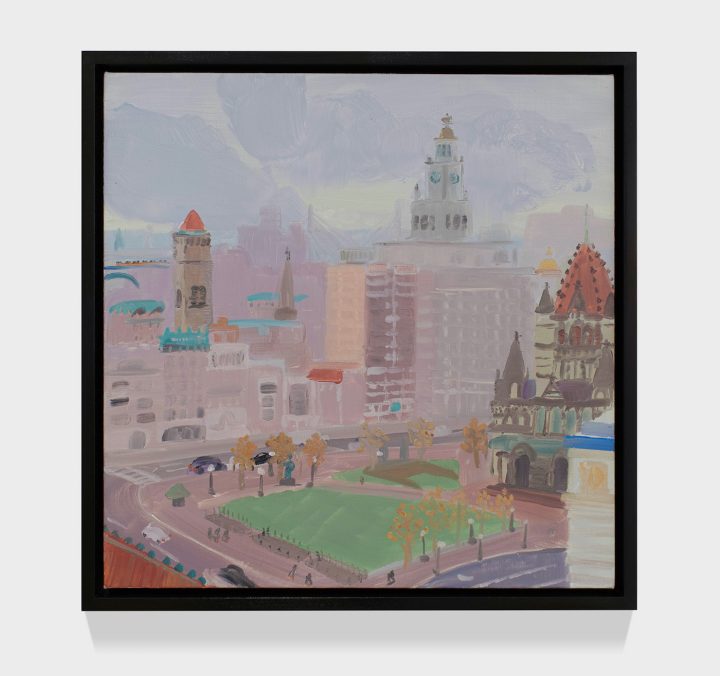

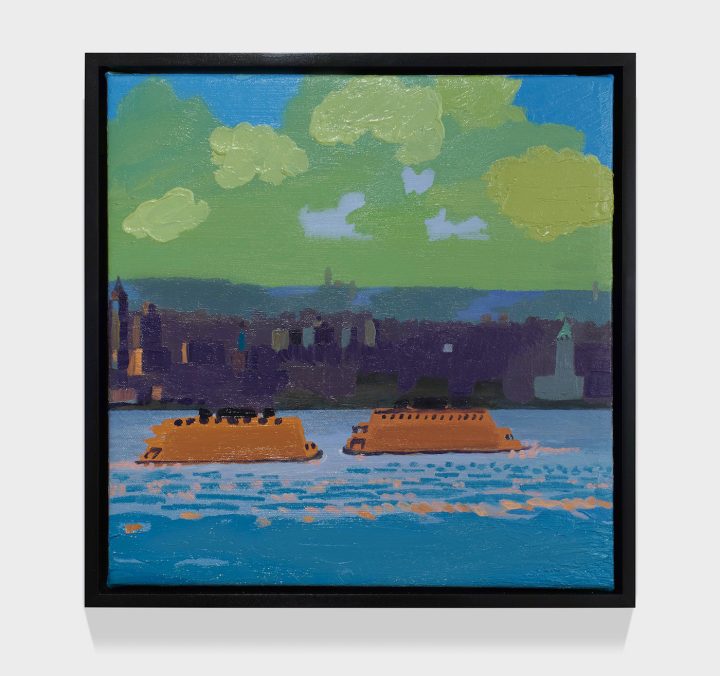

Meandering between Boston where he grew up and Brooklyn where he now lives and works, Heidkamp chose locations along the way ripe with personal meanings and, frequently, art historical references. Cityscapes, landscapes, seascapes, interiors and exteriors combined, his subjects are familiar yet tweaked to bring out their strangeness, or heightened with chromatic intensity. More poetry than description, Heidkamp’s imagery sneaks up on you: he finds unexpected ways to present recognizable subjects — the statue of the 18th century American portrait painter John Singleton Copley dissolving into the obscurity of nocturnal Boston, toy-like ferries plying the Hudson under a bright green sky, a Hopper-esque house on the Rockport coast, blown ghostly in an atmosphere of sea air and wind.

Heidkamp situates himself unabashedly within the tradition of French and American plein air painters, those who reveled in the physicality of paint and its ability to capture truths of light, mood, and weather seemingly on the fly. The nods to earlier masters are apparent everywhere. We see glimmers of Claude Monet, Edward Hopper, Marsden Hartley, Milton Avery, George Bellows, Jane Freilicher, Fairfield Porter, even the living patriarch of painterly realism Alex Katz. It’s as if Heidkamp is in easy, relaxed conversation with them all. Neither refuting, mimicking, nor appropriating his predecessors, his radicality lies in an “all in,”irony-free affirmation of the enduring relevance of intense looking, combined with exuberant mark-making — and their combined capacity to snap us awake and reset our ability to see.

I found the strongest paintings to be those with the most redolent atmosphere of unplugged longing. Heidkamp does dusk with aching poignancy, in part due to a penchant for a haunting blue (Prussian blue? Phthalo blue?) that saturates oddly compelling, off-kilter compositions. It’s an affecting strategy — conjuring that fleeting hour of the day when the world puts on its most dazzling performance just before the stage goes dark.

In “Windsor Terrace” (2017), a foreshortened trellised archway in the foreground acts as a gateway into the darkening horizon, while above, fiery pink clouds are ignited by the sun’s last rays. Even if you didn’t know, as I later learned, that just beyond the distant row of trees lies Brooklyn’s Greenwood Cemetery (the subject of an earlier body of work), the painting delivers a subtle foreboding sense of life as a briefly illuminated passageway en route to its final destination.

The empty twilight interior “Boston Library” (2017) — its dark vaulted reading room drained of its purpose, its staff and readers gone home — is filled with strange night lights dimly lit along the walls, while the crepuscular gleam of sky, painted a deep, heart-stopping blue, is glimpsed through the windows. A white flag stripped of stars and stripes — a startling detail — hangs limp outside. Is it going too far to suggest that this image, painted in the crucible of these troubled political times, can be read as a site of knowledge and truth lying idle, waiting for the dawn of a new era when people will care about such things again?

Especially moving is “JSC Blue” (2017), the statue of John Singleton Copley in its eponymous Boston square deserted at nightfall. The scene is suffused in a deep azure haze, the painter’s heroic posture reduced to a dark generic silhouette, the palette and brushes in his hand barely visible. Whatever remaining dignity left to Copley is further diminished by the gentle mockery of a bird perching on his head. Heidkamp must have felt a sense of identification with his subject, a fellow artist, sharing a plein air moment together, the contemporary one finishing his painting, the historical one consigned to plein air in perpetuity, while history moves indifferently on.

Heidkamp applies oil paint in a variety of ways, attuned to qualities inherent in the pigments themselves. He can make a painting seem to appear all in a breath, as in the lovely “Copley Square” (2017) in which we feel his brush flitting here and there, positing points of perfectly calibrated color, coalescing in an airy sense of place and weather. He can go thick and visceral, invoking Marsden Hartley, laying the paint on in glistening impasto, as in “Starlight West Village” (2017), in which the color sings with the kind of innocent bravado of an outsider artist. The“just rightness” of his color choices, even the quirkier ones, as well as his withholding of just enough visual information to suspend our disbelief, mimics the gauzy subjective way we actually see, and keeps the focus on his intent: to conjure an emotionally resonant atmosphere.

Taking stock of the paintings in Boston to Brooklyn in the context of Heidkamp’s work to date, one can sense an altered tone, more melancholy and subdued. It registers as more in keeping with Yankee sobriety than the jazzed, almost hallucinatory high-key color and whimsical flights of imagination animating his earlier work. Perhaps this shift has resulted in part from the structured parameters of the Met’s Talking Pictures show, and the subtle influence of the constant visual conversation with his painting partner Cynthia Daignault; or it might have been because the six month project took place during a Northeast winter — an austere season, especially challenging to a plein air painter!

But perhaps the most profound influence was that the timing of their collaboration coincided exactly with the election of Donald Trump and its aftermath. The shock and grief most artists felt caused many, including Heidkamp and Daignault (as Heidkamp confirmed to me during an informal interview), to question the purpose of making art when the country was in crisis. It was a collective moment of deep reflection and anguished soul-searching, and it shows in these paintings.

Serious plein air artists like Heidkamp, who are cognizant of 20th and 21st century shifts in the language and intent of painting, yet choose to take on the furious flux of the upwelling world, are staking out a territory that represents — in the full sense of re-presenting — an art that joins what we see with what we feel. It refutes fake news, declaring instead, “I was here, I saw this, I felt this!”It pushes back against postmodern claims there is no truth, thus reclaiming — not Truth in a monolithic sense — but the authentic truths of individual human experience.

Even the tough-minded practitioner of plein air painting Rackstraw Downes, still working from life at the age of seventy-eight with his unflinching vision of industrial blight, has written in his essay, “What the Sixties Meant to Me” about the work he does: “Do not all aesthetic judgments boil down in the end to statements of what you love?”

In Heidkamp’s case, his project carries a welcome sense of slowing time down, and a desire for sensual and psychic reconnection to our visible surroundings. Sometimes painting that speaks with immediacy and verve of attachment to this world is just what we need to see.

O Artigo: Translating Sight into Paint, foi publicado em Hyperallergic

The Post: Translating Sight into Paint, appeared first on Hyperallergic

Assinados por Artes & contextos, são artigos originais de outras publicações e autores, devidamente identificadas e (se existente) link para o artigo original.

Ajuda-nos a manter viva e disponível a todos esta biblioteca.