What makes one join in protest against an injustice suffered by another? And what makes someone else unable to understand the necessity of these demonstrations? These are the central questions considered in The Window and the Breaking of the Window, a new exhibition of black American artists at the Studio Museum in Harlem — and they’re questions more crucial than ever to ask as the Trump administration takes power over an increasingly Balkanized American society.

When the Black Lives Matter protests first began in the summer of 2013, they were initially prompted by the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the killing of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin. Zimmerman perceived Martin’s blackness as inherently suspicious, and his acquittal affirmed that his fearful perspective is shared by the American justice system. This illusory perception of black Americans isn’t new. Ralph Ellison wrote about it back in 1952 in his luminous novel, Invisible Man, where his nameless protagonist tells the reader, “It is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass.” And protests against such a limited allowance of black identity aren’t new either; they animated the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, and added fuel to the fire of the culture wars of the ‘90s. Now, The Window and the Breaking of the Window asks its visitors to reexamine their understanding of the intersection of personal identity and mass demonstrations in America.

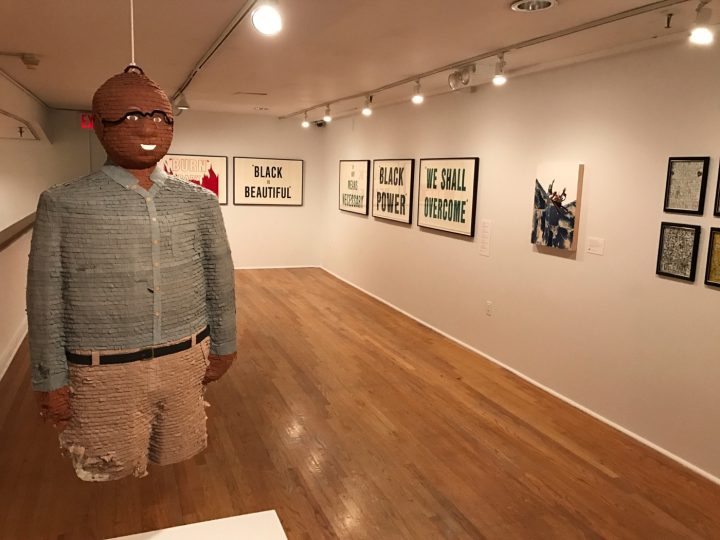

The most striking piece in the small exhibition is Dave McKenzie’s “Self-Portrait Piñata” (2002). Beaten to nothingness below the waist, the figure, with blank, brown circles for eyes and a white slice of card stock for a smile, hangs from the ceiling by a knotted rope and spins around, moved by both the changing air currents and the numbers of visitors circulating through the gallery. The papier-mâché dummy is a caricature of compliance, embodying the idealized black man of the white hegemony’s imagination, or seen through the white supremacist’s window: a black life that matters only insomuch as it serves as entertainment and effigy. But this straw man is ultimately empty, there are no candy entrails spilled below.

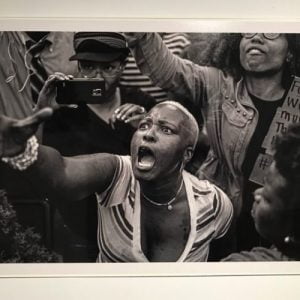

If McKenzie’s self-portrait gives us the glaring window, then Devin Allen’s rich, black-and-white photographs of protests in Baltimore move towards the shattering of it. A 25-year-old Baltimore resident, Freddie Gray, suffered a fatal injury while in police custody, and his death sparked the demonstrations pictured in the five prints on display. Allen, a local to the city and, at 28, not much older than Gray, shares in the pain and perseverance of his subjects. His most affecting images deal in specificity: a single figure floating on a sea of raised hands, holding his own fists high into the empty expanse above; a wailing woman reaching out past the camera, the sweat of her stress shining like silver on her outstretched arm and forehead.

But the most famous of Allen’s images on display – a shot showing a wall of riot-ready police charging an anonymous figure fleeing in the foreground – focuses less on the particularities of the protesters than on the forces they face. The image ran on the front cover of Time magazine beneath the caption, “America, 1968” with the antiquated year crossed out and “2015” added in red ink. Drawing these parallels through time can have value, but there are problems with such a macro perspective as well. History may seem cyclical, but it builds upon itself, and pressures unrelieved over time compound until they can be contained no longer. A series of relief prints by the artist Kerry James Marshall illustrates this problem by emphasizing common messages of American protests divorced from the people and specific moments of protest that give them power. Framed behind glass within the quiet of the gallery, the aggressive phrases: “Burn Baby Burn,” or even “By Any Means Necessary,” become lifeless platitudes without the individuals to bring them to life.

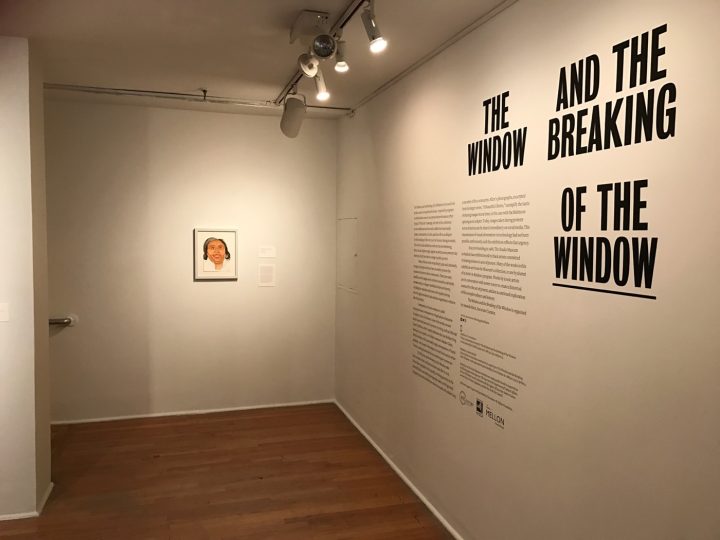

At the opposite end of the thematic spectrum from Marshall’s prints, are Rudy Shepherd’s lovingly rendered watercolor portraits of victims and perpetrators of racial violence. Each portrait is displayed for one week and then switched for another; when I visited in the first week of January I encountered Cynthia Hurd’s image. Before she became one of the nine churchgoers killed by Dylann Roof in Charleston, before she became one of the 475 people killed in one of the 372 American mass shooting incidents of 2015, Cynthia was the matriarch of her family, a dedicated librarian for 31 years, and a giggly gossip. Her sweet-natured sass exudes from the painting’s depiction of her warm eyes, bunched, blushing cheeks, and inquisitive smirk, as if she were on the verge of divulging some juicy secret.

Another portrait depicts Mike Brown, the unarmed, 18-year-old gunned down by officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson. Wilson envisioned Brown as “a demon” before he shot him, and the ensuing protests mythologized Brown into an idol. Ellison’s invisible protagonist might say the world saw “everything and anything except [him].” Shepherd’s tenderly painted portrait shows Brown, not as a monster or martyr — some flat symbol to rally behind or against — but as a young man in all his actuality, in all his coy and colorful complexity.

Shepherd’s portraits exemplify the fundamental message of The Window and the Breaking of the Window: that the recognition of a shared humanity between observer and object, between one and the Other, isn’t something that should have to be pleaded for in protests. It’s something innate and inalienable to a just and equitable society. This recognition promotes a radical empathy that engages the unaffected in understanding the urgency of present-day protests, and asks them, along with the affected, to act communally to defend a universal dignity.

Ajuda-nos a manter viva e disponível a todos esta biblioteca.

The Window and the Breaking of the Window continues at the Studio Museum in Harlem (144 West 125th Street, Harlem, Manhattan) through March 5.

O Artigo: The Power of Protest Art and the Dignity of the Protester, foi publicado em Hyperallergic

The Post: The Power of Protest Art and the Dignity of the Protester, appeared first on Hyperallergic

Assinados por Artes & contextos, são artigos originais de outras publicações e autores, devidamente identificadas e (se existente) link para o artigo original.