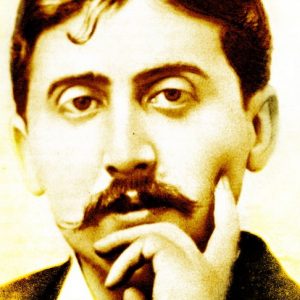

Marcel Proust

“The end of a book’s wisdom appears to us as merely the start of our own, so that at the moment when the book has told us everything it can, it gives rise to the feeling that it has told us nothing.”

Ajuda-nos a manter viva e disponível a todos esta biblioteca.

How is it that tiny black marks on a white page or screen can produce such enormous ripples in the heart, mind, and spirit? Why do we lose ourselves in books, only to find ourselves enlarged, enraptured, transformed? Galileo saw reading as a way of attaining superhuman powers. Half a millennium later, his modern counterpart Carl Sagan extolled books as“proof that humans are capable of working magic.” For Kafka, they were “the axe for the frozen sea within us.”For the poet Mary Ruefle, “someone reading a book is a sign of order in the world.” “A book is a heart that beats in the chest of another,” Rebecca Solnit wrote in her lyrical meditation on why we read and write.

One of the truest and most beautiful answers to this perennial question comes from Marcel Proust (July 10, 1871–November 18, 1922).

By his mid-twenties, Proust had already published pieces in prestigious literary journals. But he was yet to write a novel. When he was twenty-six, a thousand pages into his first attempt, he found himself stumped and unable to make the book cohere. That’s when he discovered the great Victorian art critic John Ruskin, whose writings blew his mind open.

Over the next three years, Proust immersed himself in Ruskin’s prolific body of work and, despite his imperfect English, set about translating into French the books that had most moved him, obsessively annotating them with footnotes. Many years later, Proust would come to write in the seventh and final volume of In Search of Lost Time, his now-legendary novel building on the themes he had attempted to explore in that frustrated first attempt:

I realised that the essential book, the one true book, is one that the great writer does not need to invent, in the current sense of the word, since it already exists in every one of us — he has only to translate it. The task and the duty of a writer are those of a translator.

Proust’s translations of Ruskin took on a life of their own. They came to embody what the great Polish poet and Nobel laureate Wisława Szymborska, in the discussing the translation of her own work, extolled as “that rare miracle when a translation stops being a translation and becomes … a second original.” The preface to one of his Ruskin translations became a second original so miraculous that it was eventually published separately as On Reading (public library). In it, Proust considers the pleasurable paradoxes of reading:

Reading, unlike conversation, consists for each of us in receiving the communication of another thought while remaining alone, or in other words, while continuing to bring into play the mental powers we have in solitude and which conversation immediately puts to flight; while remaining open to inspiration, the soul still hard at its fruitful labours upon itself.

He contemplates the irrepressible, universal pleasure of childhood reading:

There are perhaps no days of our childhood that we lived as fully as the days we think we left behind without living at all: the days we spent with a favourite book. Everything that filled others’ days, so it seems, but that we avoided as vulgar impediments to a sacred pleasure — the game for whose sake a friend came looking for us right at the most interesting paragraph; the bothersome bee or sunbeam that forced us to look up from the book, or change position; the treats we had been forced to bring along but that we left untouched on the bench next to us while above our head the sun grew weaker in the blue sky; the dinner we had to go home for, during which we had no thought except to escape upstairs and finish, as soon as we were done, the interrupted chapter — our reading should have kept us from perceiving all that as anything other than obtrusive demands, but on the contrary, it has graven into us such happy memories of these things (memories much more valuable to us now than what we were reading with such passion at the time) that if, today, we happen to leaf through the pages of these books of the past, it is only because they are the sole calendars we have left of those bygone days, and we turn their pages in the hope of seeing reflected there the houses and lakes which are no more.

Proust echoes Hermann Hesse’s elegant case for why the highest form of reading is non-reading and considers the supreme reward of reading:

This is one of the great and wondrous characteristics of beautiful books (and one which enables us to understand the simultaneously essential and limited role that reading can play in our spiritual life): that for the author they may be called Conclusions, but for the reader, Provocations. We can feel that our wisdom begins where the author’s ends, and we want him to give us answers when all he can do is give us desires. He awakens these desires in us only when he gets us to contemplate the supreme beauty which he cannot reach except through the utmost efforts of his art… The end of a book’s wisdom appears to us as merely the start of our own, so that at the moment when the book has told us everything it can, it gives rise to the feeling that it has told us nothing.

In a sentiment that calls to mind Susan Sontag’s assertion that books “give us the model of self-transcendence… a way of being fully human,” Proust suggests that a great book shows us the way to ourselves, and beyond ourselves:

Reading is at the threshold of our inner life; it can lead us into that life but cannot constitute it.

[…]

What is needed, therefore, is an intervention that occurs deep within ourselves while coming from someone else, the impulse of another mind that we receive in the bosom of solitude.

O Artigo: Proust on Why We Read, foi publicado em Brainpickings.org

The Post: Proust on Why We Read, appeared first on Brainpickings.org

Assinados por Artes & contextos, são artigos originais de outras publicações e autores, devidamente identificadas e (se existente) link para o artigo original.