“However used to fame a great artist may be, he cannot be insensible to a sincere compliment, especially when that compliment is like a cry of gratitude.”

BY MARIA POPOVA

Ajuda-nos a manter viva e disponível a todos esta biblioteca.

“After silence that which comes nearest to expressing the inexpressible is music,” Aldous Huxley wrote in his enthralling meditation on the power of music, adding:“When the inexpressible had to be expressed, Shakespeare laid down his pen and called for music.” Nietzsche believed that “without music life would be a mistake”— perhaps the most extreme addition to the extensive canon of great writers extolling the power of music.

But perhaps the sincerest, most beautiful, most touching testament to the power of music came not in the form of a pointed essay but in a letter — that most intimate and immediate packet of sentiment.

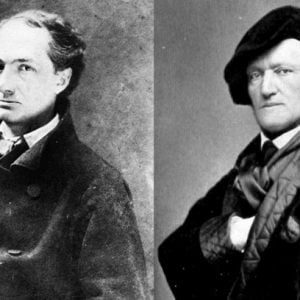

A century before Albert Camus reached across the Iron Curtain to Boris Pasternak for a warm embrace of appreciation, his compatriot Charles Baudelaire (April 9, 1821–August 31, 1867) reached across another cultural divide to pay his gratitude for the transcendent gift of music. A thirty-eight-year-old Baudelaire, not yet celebrated as one of the finest poet-philosophers who ever lived, sent the great German composer and conductor Richard Wagner (May 22, 1813–February 13, 1883) a largehearted letter of appreciation, later included in The Conquest of Solitude: Selected Letters of Charles Baudelaire (public library). It stands as a touching testament to both the power of music and the power of a generous gesture.

Baudelaire writes on February 17, 1860:

Dear Sir:

I have always imagined that however used to fame a great artist may be, he cannot be insensible to a sincere compliment, especially when that compliment is like a cry of gratitude; and finally that this cry could acquire a singular kind of value when it came from a Frenchman, which is to say from a man little disposed to be enthusiastic, and born, moreover, in a country where people hardly understand painting and poetry any better than they do music. First of all, I want to tell you that I owe you the greatest musical pleasure I have ever experienced. I have reached an age when one no longer makes it a pastime to write letters to celebrities, and I should have hesitated a long time before writing to express my admiration for you, if Id did not daily come across shameless and ridiculous articles in which every effort is made to libel your genius. You are not the first man, sir, about whom I have suffered and blushed for my country. At length indignation impelled me to give you an earnest of my gratitude; I said to myself, “I want to stand out from all those imbeciles.”

In a sentiment that calls to mind Anthony Burgess’s recollection of how he fell in love with music as a little boy — Burgess wrote of “a psychedelic moment… an instant of recognition of verbally inexpressible spiritual realities” — Baudelaire recounts how Wagner first enchanted him:

The first time I went to the Italian Theatre in order to hear your works, I was rather unfavorably disposed and indeed, I must admit, full of nasty prejudices, but I have an excuse: I have been so often duped; I have heard so much music by pretentious charlatans. But you conquered me at once. What I felt is beyond description, and if you will be kind enough not to laugh, I shall try to interpret it for you. At the outset it seemed to me that I knew this new music, and later, on thinking it over, I understood whence came this mirage; it seemed to me that this music was mine, and I recognized it in the way that any man recognizes the things he is destined to love. To anybody but an intelligent man, this statement would be immensely ridiculous, especially when it comes from one who, like me, does not know music.

Baudelaire is echoing Tolstoy’s famous theory of art, in which the great Russian author asserted that emotional “infectiousness” is the single most significant criterion for great art. But he is also far ahead of his time — the word “empathy” only entered the popular lexicon half a century later and was first used to describe the imaginative act of projecting oneself into a work of art, inhabiting it, possessing it whilst being possessed by it in much the same way that Baudelaire did Wagner’s music.

In language strikingly reminiscent of how astronauts describe the cosmic awe of “the overview effect,” Baudelaire articulates the transcendent effect Wagner’s music had on him:

The thing that struck me the most was the character of grandeur. It depicts what is grand and incites to grandeur. Throughout your works I found again the solemnity of the grand sounds of Nature in her grandest aspects, as well as the solemnity of the grand passions of man. One feels immediately carried away and dominated.

Writing a generation before Oscar Wilde made his memorable case for why a “temperament of receptivity” is essential for savoring art, Baudelaire attests to how this willing receptivity, which great art unleashes in its audience, swings open the doors of perception:

Quite often I experienced a sensation of a rather bizarre nature, which was the pride and the joy of understanding, of letting myself be penetrated and invaded — a really sensual delight that resembles that of rising in the air or tossing upon the sea. And the music at the same time would now and then resound with the pride of life. Generally these profound harmonies seemed to me like those stimulants that quicken the pulse of the imagination… There is everywhere something rapt and enthralling, something aspiring to mount higher, something excessive and superlative. For example, if I may make analogies with painting, let me suppose I have before me a vast expanse of dark red. If this red stands for passion, I see it gradually passing through all the transitions of red and pink to the incandescent glow of a furnace. It would seem difficult, impossible even, to reach anything more glowing; and yet a last fuse comes and traces a whiter streak on the white of the background. This will signify, if you will, the supreme utterance of a soul at its highest paroxysm.

Baudelaire ends by reminding Wagner of the grand and heartbreaking truth of artistic appreciation: that most of it happens in the shadows, in the sinews, in the silence of private experiences, and that artists only ever glimpse a fraction through the grateful words of the few willing to return the gift by articulating those ineffable but transformative experiences that the artist has afforded them. Baudelaire writes:

From the day when I heard your music, I have said to myself endlessly, and especially at bad times, “If I only could hear a little Wagner tonight!” There are doubtless other men constituted like myself… Once again, sir, I thank you; you brought me back to myself and to what is great, in some unhappy moments.

Ch. Baudelaire

I do not set down my address because you might think I wanted something from you.

Complement with Baudelaire on the genius of childhood, beauty and strangeness, and his increasingly timely open letter to the privileged about the political power of art, then revisit other luminous beams of appreciation between great minds: Isaac Asimov’s fan mail to young Carl Sagan, Charles Dickens’s letter of admiration to George Eliot, teenage James Joyce’s grateful letter to Ibsen, his great hero, Darwin’stouching letter of appreciation to his best friend and greatest supporter, and the virtuous cycle of mutual admiration between Thomas Mann and Hermann Hesse.

O Artigo: A Cry of Gratitude: Baudelaire’s Magnificent Fan Mail to Wagner, foi publicado em Brainpickings.org

The Post: A Cry of Gratitude: Baudelaire’s Magnificent Fan Mail to Wagner, appeared first on Brainpickings.org

Assinados por Artes & contextos, são artigos originais de outras publicações e autores, devidamente identificadas e (se existente) link para o artigo original.