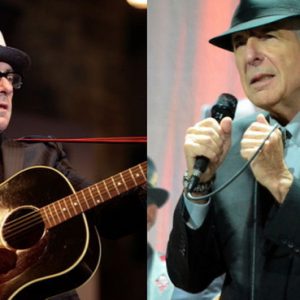

In every musician’s discography, one album has to rank at the bottom. In the case of the prolific and respected singer-songwriter Elvis Costello, fans and critics alike tend to single out 1984’s Goodbye Cruel World, which even Costello himself once described as “our worst album.” But with an artist like him doing the creating, even the duds hold a certain interest, or have a value at their core that emerges in unexpected ways. “Among the most discordant songs on the album was the forgettable ‘The Deportees Club.’ But then, years later, Costello went back and re-recorded it as ‘Deportee,’ and today it stands as one of his most sublime achievements.”

That comes from “Hallelujah,” a recent episode of Revisionist History, the new podcast from Malcolm Gladwell that we first featured back in June. Here, perhaps the best-known curious journalistic mind of our time asks where genius comes from. Or, less abstractly, he asks about “the role that time and iteration play in the production of genius, and how some of the most memorable works of art had modest and undistinguished births.” His other example from the realm of music gives the episode its title. It first appeared, in the same year as did Costello’s “The Deportees Club,” on Leonard Cohen’s Various Positions, not making much of an impact until a cover by John Cale, and then more so one by Jeff Buckley, made it the “Hallelujah” we know today.

“That’s awful,” moans Gladwell, cutting off a clip of Costello’s original “The Deportees Club” — this from a self-described Elvis Costello superfan, who in 1984 bought Goodbye Cruel World the week it came out, just like he bought every other Elvis Costello album the week it came out. He regarded it as unlistenable then and still regards it as unlistenable today, applying that adjective at least twice in this podcast alone. He goes easier on Cohen’s original “Hallelujah,” poking fun at its dirge-like seriousness. Then, being Malcolm Gladwell, he goes on to frame the story of how both songs became great—the former a personal obsession of his own, the latter a phenomenon covered by “nearly everyone”—in terms of a theory: some artists are Picasso, and others are Cézanne.

Ajuda-nos a manter viva e disponível a todos esta biblioteca.

Artists of the Picasso model execute their works seemingly at a stroke, often after long periods spent consciously or unconsciously assembling a coherent vision. Artists of the Cézanne model execute, execute, and execute again, refining their way from an imperfect first product to a much more perfect final one. Sometimes the first iteration a Cézanne puts out emerges at the wrong time, the initial fate of “The Deportees Club” and “Hallelujah.” Neither song, each by a musician in his own way unsuited to the climate of pop perfectionism that prevailed in the mid-1980s, found its form right away. Both would fit well into an institution I’ve long dreamed of called the Museum of First Drafts: enter and behold just how far a creation still needs to go even after its “creation”—even when created by a Costello, a Cohen or a Cézanne.

O Artigo: Malcolm Gladwell on Why Genius Takes Time: A Look at the Making of Elvis Costello’s “Deportee” & Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah”, foi publicado em Open Culture

The Post: Malcolm Gladwell on Why Genius Takes Time: A Look at the Making of Elvis Costello’s “Deportee” & Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah”, appeared first on Open Culture

Assinados por Artes & contextos, são artigos originais de outras publicações e autores, devidamente identificadas e (se existente) link para o artigo original.