(all watercolors by the author for Hyperallergic)

I wait around in the Italian Center for Modern Art’s kitchen before the tour of the Giorgio Morandi exhibition begins. We are offered espresso or coffees in bright Pantonue cps, which we gladly accept. “This space was designed to experience slow art, and to feel like you are living with the works of art,” the graduate fellow who will be giving us the tour says.

The experience feels like a hunt for clues about how Morandi worked. On the kitchen walls hang photographs by Joel Meyerowitz of the objects Morandi used to paint in his studio: a round vase, a stout cup, a conical vessel. I am especially drawn to a rich blue vase attached to the base of a chalice. Morandi painted most of his glass objects white, which would have made it easier for him to control the reflections and the light. Sometimes, he made his own objects to explore different shapes in his paintings. In the gallery, on top of a black podium, is one of such objects, which he fashioned together out of scraps of metal.

We are now in a brightly lit room, furnished with designer couches and coffee tables. During the tour, I sit on the sofa while observing the paintings. The atmosphere is comfortable and homey, like we are sitting in an elegant and sparsely furnished living room.

Morandi’s earlier paintings have a subdued palette. Some of the objects are shown volumetrically, some two dimensionally, and sometimes I cannot make sense of the different volumes. The more I look at the paintings, the more I notice the blurring of shapes. An object that initially appears to be in the foreground, is actually not an object at all, but is a void, the negative space between volumes. “Morandi created a sealed atmosphere, as if it were a clay tablet that he is pressing the objects into. He is creating a stage of reality,” the graduate fellow says.

I think about what the fellow said, and how each of Morandi’s paintings, and every step he took along the way to make them, is meditated, composed, specific. But the images at once resemble our reality and escape it.

In the ‘50s and ‘60s, Morandi painted more than 700 paintings, or one a week. His diligence and methodical routine is something I find inspiring, as I strive to apply it to my own daily watercoloring habit. Even the pricing of his paintings was controlled: the value fluctuated according to the number of objects in the image, which often varied from one to three.

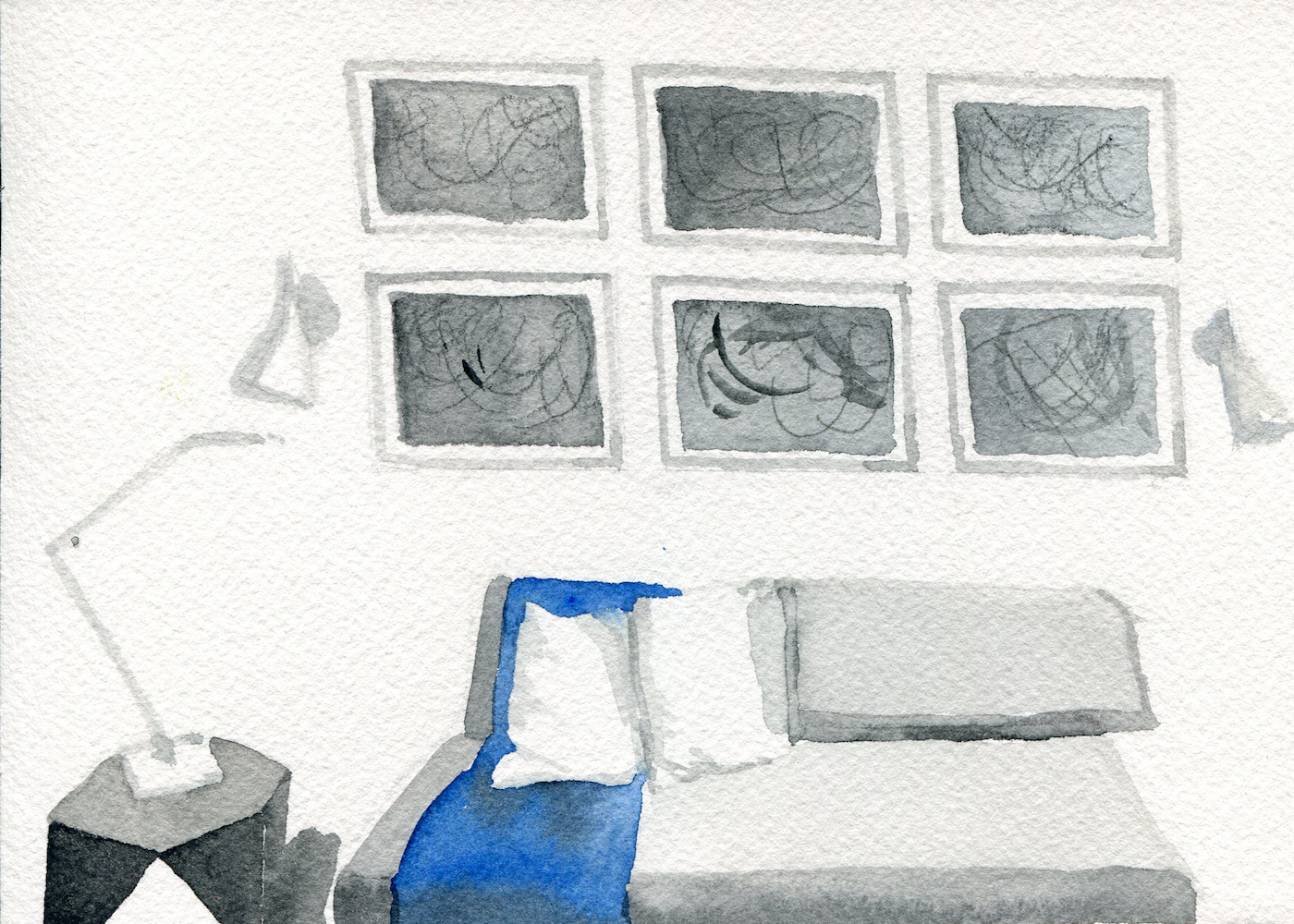

After the tour is over, I peak into one of the gallery offices. It is a large, sunlit room, decorated with a gray couch, and an array of black-and-white photographs taken by Tacita Dean of the swirly markings Morandi created on his table to notate the precise positioning of his objects. This makes me realize how calculated the spacing of his objects really is; it shifts only slightly from painting to painting, as the scribbled circles overlap with each other in a way that reminds me of those spin top marker toys I used to play with as a child.

Ajuda-nos a manter viva e disponível a todos esta biblioteca.

I enter the elevator and as the doors are closing my last view is of a photograph of Morandi’s palette taken by Matthias Schaller, which is just a smear of faded white on a wooden board. Morandi wiped it clean every evening, so that he could start with a fresh batch of colors each morning. I cannot relate to this, as I let my palette accumulate with colors that blend slowly over time, allowing new colors to mix in a sometimes accidental way. (Basically I do not have the patience to clean my palette every day.) I admire his precision and exacting method for selecting his colors. For him, nothing was left to chance.

Giorgio Morandi continues at the Italian Center for Modern Art (421 Broome St, Soho, Manhattan) through June 25.

O Artigo Pondering and Painting Giorgio Morandi’s Precise Compositions, foi publicado em: Hyperallergic

The post Pondering and Painting Giorgio Morandi’s Precise Compositions, appeared first on: Hyperallergic

Assinados por Artes & contextos, são artigos originais de outras publicações e autores, devidamente identificadas e (se existente) link para o artigo original.